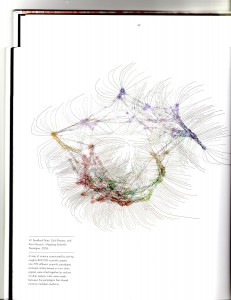

I’ll preface this post by saying that even after reading Manuel Lima’s immensely readable chapter introducing networks in Visual Complexity, I am not entirely certain that I understand the purpose of most network visualizations. On second thought, perhaps I don’t understand the outcome of most network visualizations. But before I get into that, let’s take a look at what Lima has to say about them.

What is a network?

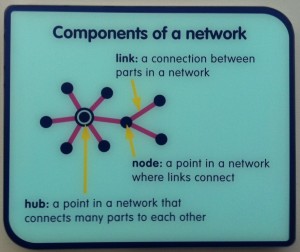

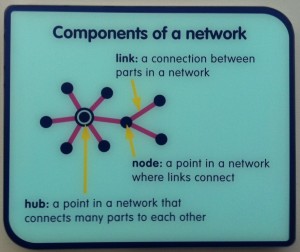

"Components of a Network," exhibit label at the New York Hall of Science

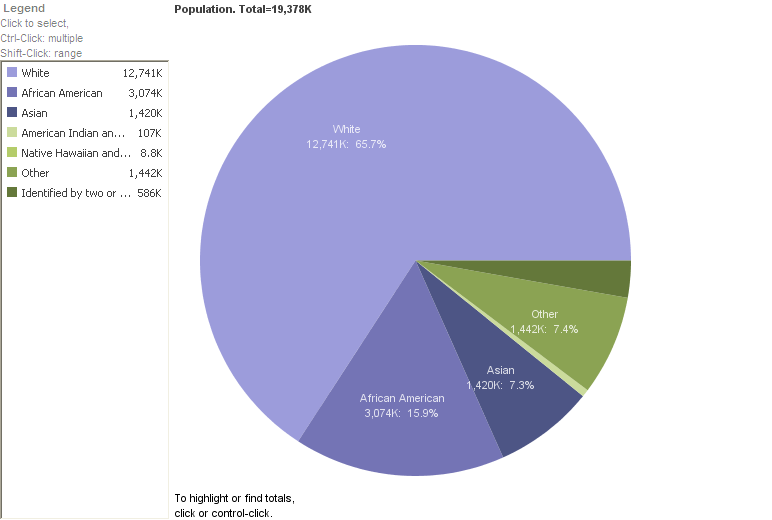

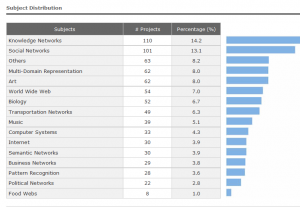

A network is a structural and organizational model of natural or artificial systems that is characterized by “a multitude of interconnecting elements” (73). Lima reviews the origins of network science, from graph theory and statistical mapping to sociometry (later known as “social network analysis” within sociology). Today most network representation takes the form of either graph drawing as part of graph theory, or network visualization as part of information visualization. Both use graphs to show a system of nodes (or vertices) and links (or edges). In network visualization, however, there is an emphasis on visual design principles to convey meaning that exceeds the sort of geometric representation one would find in graph theory. By examining the various nodes and links one can glean information about the network as a whole.

Network visualization can be a remarkable discovery tool, able to translate structural complexity into perceptible visual insights aimed at a clearer understanding. It is through its pictorial representation and interactive analysis that modern network visualization gives life to many structures hidden from human perception, providing us with an original “map” of the territory. (79)

Indeed, Lima spends considerable time drawing connections between network visualization and cartography, noting their shared goals: simplifying, clarifying, communicating, exploring, recording, and supporting. If cartography is an abstraction of the physical terrain, network visualization maps the invisible. Lima believes that the latter should learn from the former how to successfully combine science, aesthetics, and technique.

Why visualize networks?

We visualize information to decode complexity. Lima lists five functions of network visualization: document, clarify, reveal, expand, abstract. As noted above, network visualizations—when done well—act as discovery tools, revealing new insight or hidden patterns. Lima laments the lack of real principles for successful visualization, noting that in 1914 Willard Brinton attempted 25 rules for graphic representation that have yet to be expanded or embraced. He then provides his own eight principles for network visualization projects which I will summarize briefly here.

8 Principles for Network Visualization Projects

1. Start with a question. Throughout the project this will provide “a measure for naturally filtering the essential from the superfluous” (82).

2. Look for relevancy. The two key activities where this applies: choosing a data set and selecting a visualization method.

3. Enable multivariate analysis. This simply means to consider a variety of multiple data sets that will enrich the depth of analysis.

4. Embrace time. That is, represent time in your visualization. Lima acknowledges that this is very difficult to do, noting that it is often avoided due to its complexity.

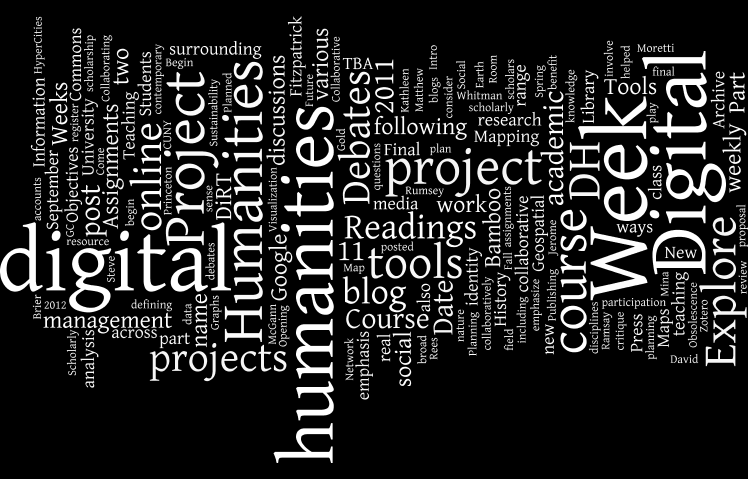

5. Enrich your vocabulary. Here Lima gives three points: make richer nodes (provide further textual information or hyperlinks in them); expressive edges (consider using length, width, color, shape, to represent information); clear visual language (e.g., use a legend, like maps do).

6. Expose grouping. Use spacial arrangement to draw attention to relationships. Drawing on psychology, Lima suggests designing visualizations based on three of the six Gestalt laws of grouping: similarity, proximity, common fate.

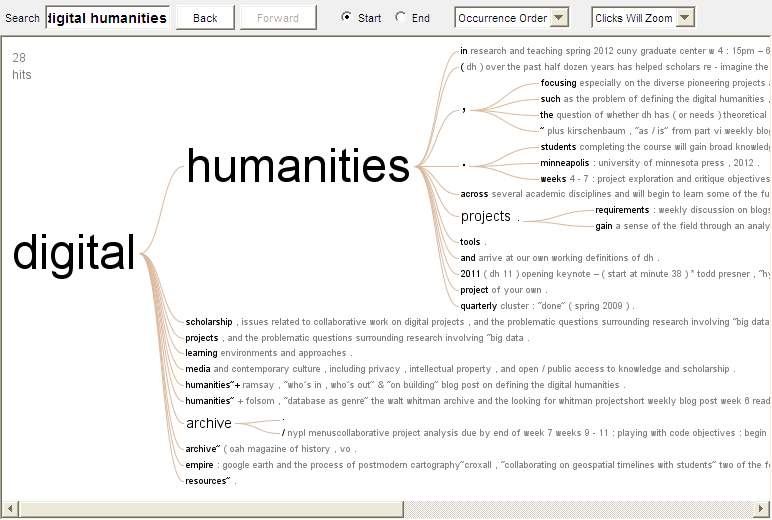

7. Maximize scaling. There are three views a network visualization can take, and Lima suggests making use of all three: macro view (reveals pattern), relationship view (shows connectivity), and micro view (depicts entities).

8. Managing intricacy. Utilize the idea of progressive disclosure, as do digital maps. Lima discusses a series of interaction design techniques: adaptive zooming (think zooming in on Google maps), overview and detail (an inset macro view on the zoomed view), focus and context (a fish-eye view that allows a zoomed area to bubble up from the remaining macro view).

Challenges for visualization

Throughout the chapter, Lima makes the case for incorporating design elements to enhance clarity and improve the manner in which the network structure is communicated to the end-user. It is not enough to build something that can manage the information; it must be usefully displayed to convey meaning. He ends with a plea for interdisciplinary design:

In order for the general usability of network visualization to improve, we need to embrace the existing body of knowledge from graphic design, cartography, and visual perception, including notions of color theory, composition, typography, layout, and spatial arrangement. (95)

On understanding network visualizations

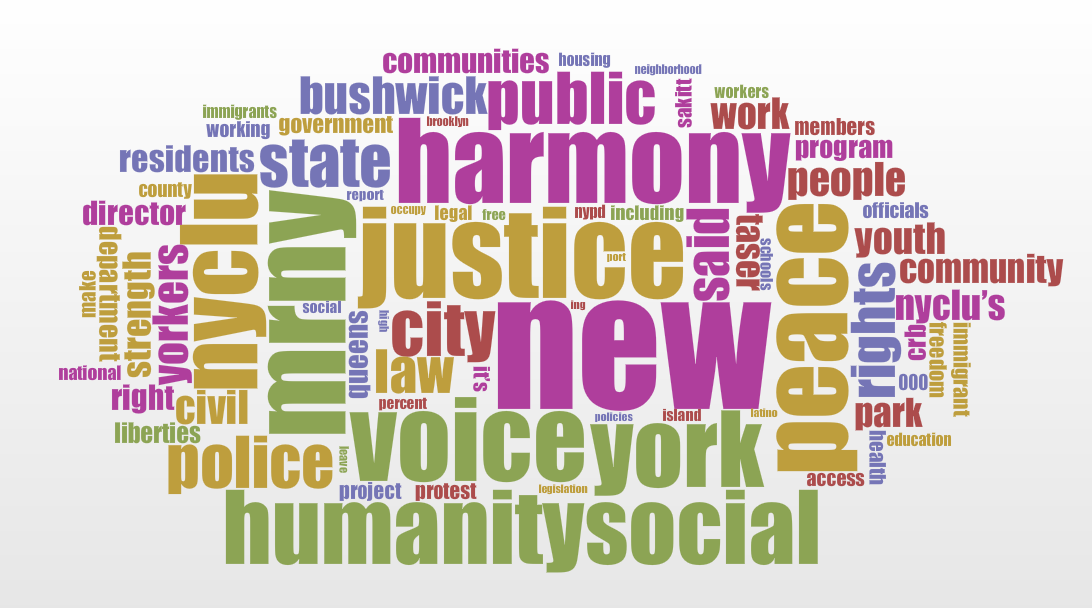

Back to my initial problem: why can’t I make sense of most network visualizations? Leafing through Lima’s book, or exploring the visualizations on the accompanying website, I am struck by their aesthetic beauty. They are gorgeous. I want to understand them. Why can’t I?

Two clues to my predicament are found in Lima’s introduction to networks. First is his call for visualizations to include an explanatory legend, in which he cautions to “beware of creating a visual language that might not be immediately recognized by everyone” (88). Second is his discussion on scaling (in Principle #7), which compares the macro view, relationship view, and micro view. He explains that the primary function of the macro view is synthesis, whereas the relationship view “is about analytics” (92). I think my problem is that I want to see the analytics, but instead I am looking at the synthesis.

Going back to the comparison with cartography, let me think about my own use of maps. Yes, they are pretty. I like to hang them on my walls. If I try to navigate unfamiliar territory using them, they certainly help. Yet they are most useful to me after I’ve explored an area by foot. Visualizing the street layout synthesizes my experience of the neighborhood and I emerge with a greater understanding of the area. This is not to say that the macro view of network visualization cannot convey meaning to me. Rather, I think I would have a better experience with them if I were first presented with detail and then allowed to zoom out to the bigger picture.

This brings me, then, to the discussion in DH of building as theory and whether or not DH projects could stand alone as scholarship for promotion and tenure (without the need for a written accompaniment). When it comes to network visualizations, I can absolutely see how the process of building advances knowledge and can be construed as the theory itself. Yet my own difficulty in reading them makes me wary of disposing entirely of that written explanation. I leave open for discussion whether or not this is a failure in usability or simply ignorance on my part.